About two weeks into our artist residency some of us started referring to Kvennaskólinn as home. We would say to each other, “I’ll see you later at home”, and “I forgot it at home”, or “I’m going home after the pool”. I saw this as a sign of how quickly we felt comfortable, supported and entrenched in our new routine during the residency: we made the residence ours – even if for only a brief time.

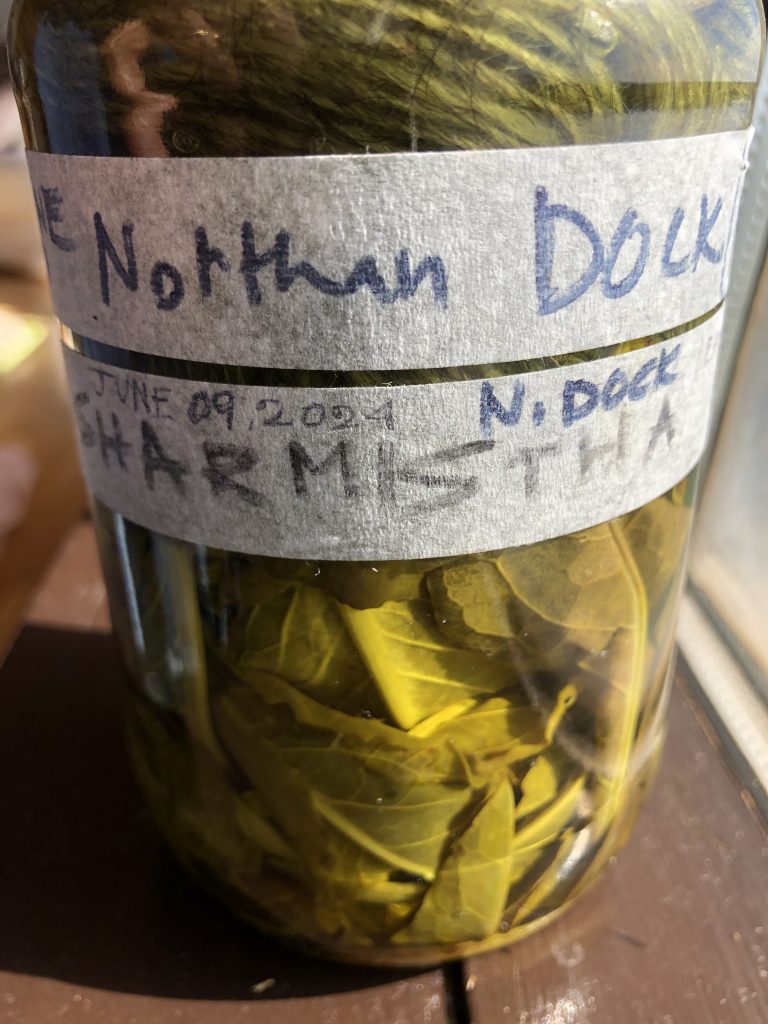

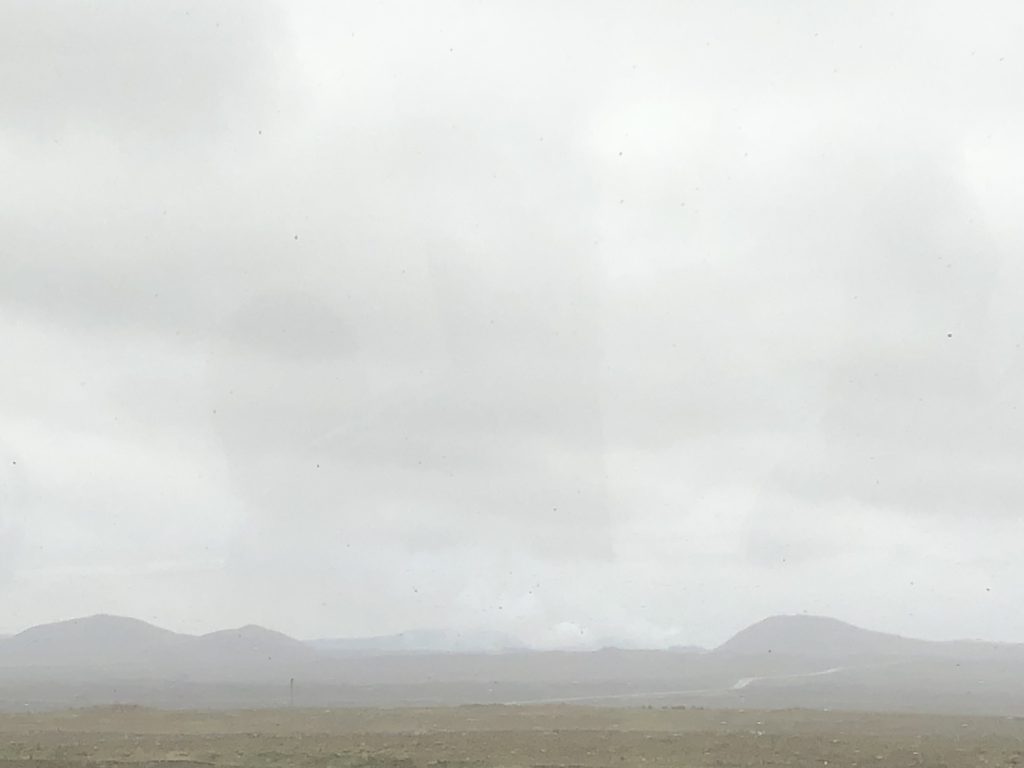

As we settled in, and got to know each other over breakfast, lunch and supper, elements of our personalities surfaced. For instance, early on the dining room table was partially taken over with puzzles that most of use would spend time, which was occasionally frustrating, trying to complete before moving on to another. One resident held marathon sessions late into the night at the table doing one puzzle after another. The table is also where we shared food. A few among us would go beyond sharing a pie bought at the store (nothing wrong with that) and cook big pots of rice and beans, waffles and banana bread pudding. Two potluck suppers with the rest of the group in the second residence led to an astonishing buffet and gave us all a chance to socialize outside of a class structure. These gatherings were not just about breaking bread, but created trust and bonds between us. We shared details about our practice, our experiences and skills, offered help, material and equipment. We became an art collective of sorts as we all created work made-in-place deeply connected to the land and water.

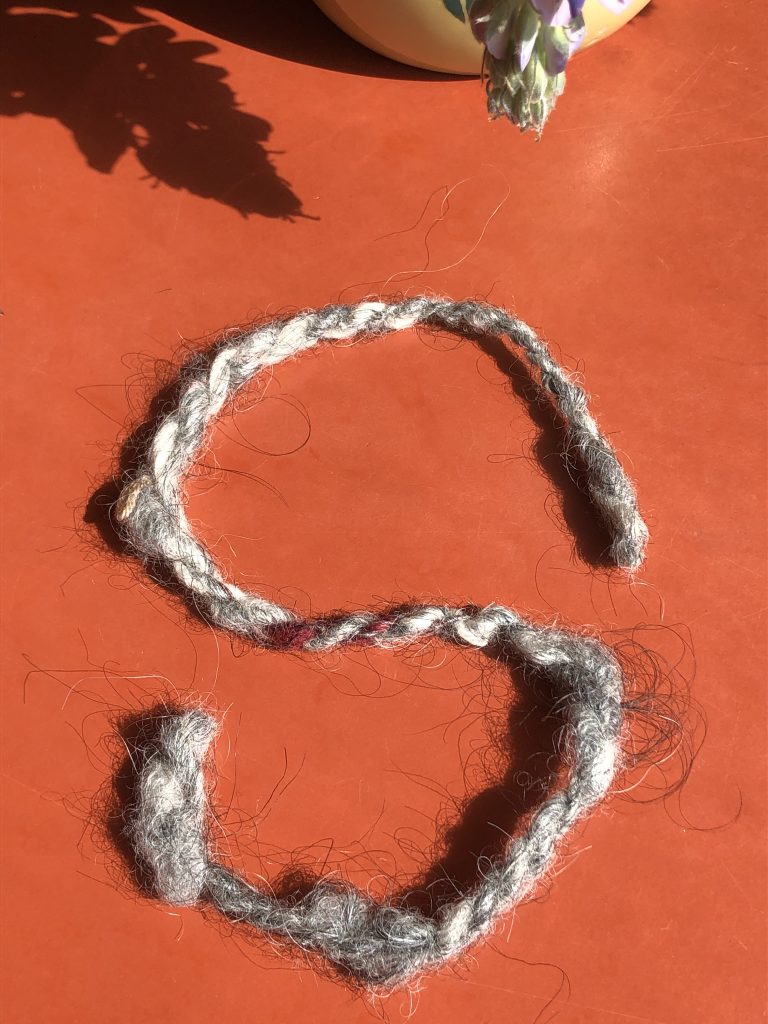

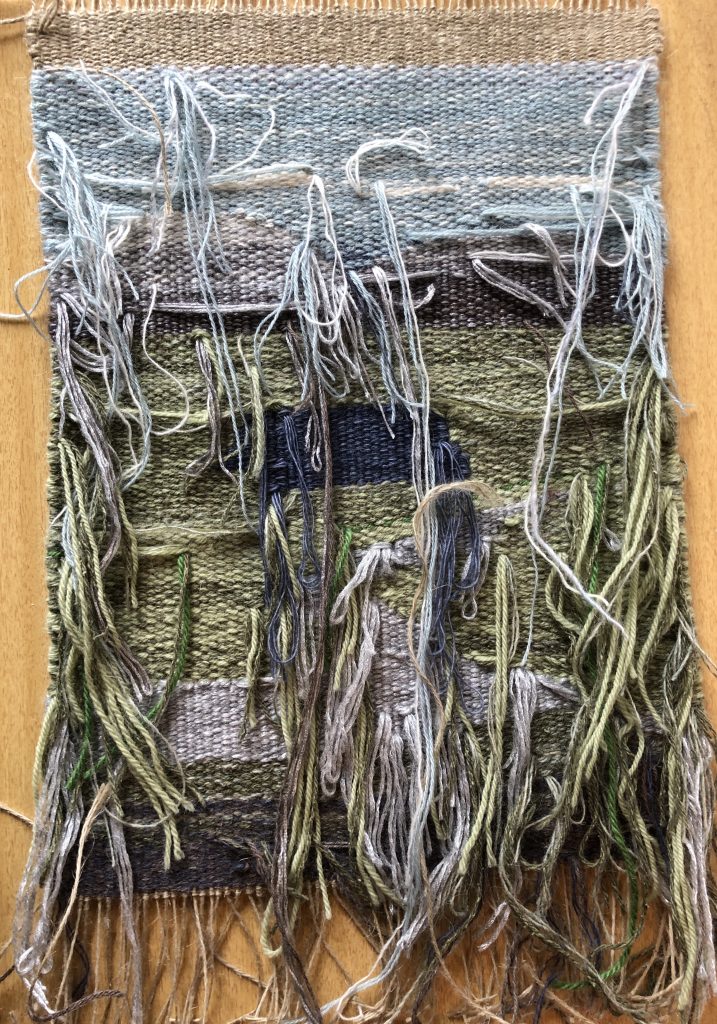

Everyone’s generosity is what stands out for me the most, and not just from the other artists, but also the staff. After explaining to Elsa, the Textile Centre’s director, that I needed a dark space to do my work, she offered me the garage at the textile lab, and she entrusted me with the key so that I could access the space anytime I needed to. This made all the difference in my ability to execute my vision for my project. Then there was Jóhanna, one of the instructors, who showed limitless patients and encouragement while teaching me to spin wool. Project manager, and horse owner, Katharina included us in a horse roundup as a group of residents moved a small herd from one pasture to another. I’ve rarely had the experience to be so close to horses, let alone while they are running at full speed. It was thrilling. Ragnheiður spent hours, and then gave us extra time, to teach us the art of tapestry. In Akureyri, both she and her daughter, Thora, came out to support a group of Concordia students among us who were holding an exhibit. I also really appreciated my conversations with Hanna, the housekeeper, who took such good care of our home.

There were moments, as I walked the halls and interacted with the staff and students on my way to my room, that I wondered if this was what it was like to be Harry Potter at Hogwarts? I may not know any spells, but there was a lots of magic inside this home. Corny, but true.

Instagram: @dalejcrockett

Website: https://www.dalecrockett.com/