From Guðrún Bjarnadóttir’s workshop to my natural dyes experiment project at The Icelandic Textile Centre.

On June 7th, some Concordia students, my professor, Kathleen Vaughan and I attended a natural dyes workshop led by Guðrún Bjarnadóttir, an Icelandic natural dryer and author of Plants of Iceland – Traditional uses and folklore. She warmly greeted all of us at her plant dyeing at Árnes við Andakílsárvirkjun in Borgarnes where the workshop took place.

She put us into groups of twos and then conducted the workshop by first giving demonstrations (e.g. how to cut rhubarb). We then boiled plants as Gudrun gave instructions. She mentioned important rules about dyeing plants i.e. respect the plants, do not take too much; never use the dye pots for cooking food; use as little chemicals as possible. Gudrun is a hands-on workshop leader, very attentive and dynamic, moreover, she loves that her workshop participants learn by doing.

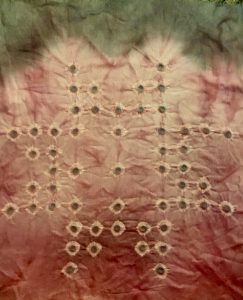

Dominique and I got spruce pine cones, which Gudrun boiled one night before the workshop as it needed more time (4-5 hours) to boil them. The second one that we boiled was rhubarb leaves. It took about an hour or so to boil them. Gudrun mentioned that using rhubarb for dyeing wool is not part of the Icelandic tradition. People imported rhubarb to Iceland as a food plant many centuries ago.

While waiting for the dyebath to be ready for dyeing, Gudrun offered us home-made food in her house. About one hour later, the dyes were ready and Gudrun took out yarn, which she had already soaked in alum overnight. The yarn was ready to be dyed and she chose white and grey wool (3 of each colour) to be dyed in the dye pots. We put the yarn in pots and waited for a while until the yarn soaked in the dyes.

In the meantime, she told us briefly about the history of plant dyeing in Iceland, icelandic plants she uses and mordants that are used to enhance the colours, such as alum, copper, creme de tartar, ammonium, chrome, iron, tin and vinegar. Copper, chrome and tin should not be used for more than sixty minutes with the yarn, and iron should not be used for more than fifteen minutes. In the old days, cow urine and human urine were used for mordant. Older urine was preferred as its pH level increased and it became more alkaline.

Gudrun, later on, prepared three dye baths for the yarn; alum, copper and ammonium, which all had strong odours. Then, she started putting the yarn into alum, copper and ammonium and asked us to track them all. Our rhubarb leaves gave a deep yellow colour, and with alum, they became bright yellow. The copper and ammonium resulted in a moss green colour.

Making dyes requires time, patience and energy, but the natural beauty of the colours as the result of the workshop was gratifying. Each plant provides an amazing diversity of shades which comes from Icelandic moss, lichen, lupin leaves, lupin flowers, heather, spruce pine cones, rhubarb leaves, rhubarb root, madder, birch, onion skin and cow parsley.

I dyed cotton and silk fabric into the dyebath that was used at the workshop. The results were different from the colours on wool. The colours used on cotton and silk ended up more pastel. Wool and silk have different fibre characteristics; therefore, the result was not the same. It is also impossible to obtain the same colour twice because of reasons such as the pH degree of soil and water, which can vary.

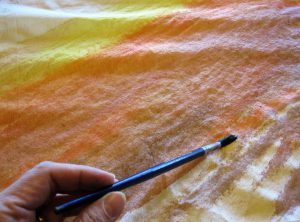

A week after the workshop, I started my natural dyes experiment from lupin flowers and leaves, using rain water and tap water. The variety of colours were produced as the result of my experiment. The dye from lupin flowers is usually greenish, but with alum as the mordant and rain water, it can be greyish. With vinegar as the mordant and rain water, it can be red purpleish. The dye from lupin leaves is usually yellow, but with mordant, it can be a deeper yellow shade.

As Gudrun mentioned having difficulties with sappan wood to produce red, I investigated the sappan wood dyeing process with rain water and tap water separately. I found that using rain water to boil sappan wood produced a deeper, clearer red. On the other hand, using tap water produced a more orange colour. With alum as a mordant, it produced a deeper orange. It’s the same case for turmeric. Using rain water to boil the turmeric produced a deeper yellow, without any mordant. Meanwhile, using tap water to boil the turmeric, produces a lighter yellow and with alum as a mordant, it becomes a deeper yellow.

A dyer should aim to create new shades, rather than to duplicate others’ results. I created different shades of colours for my artwork and labeled them as follows: lupin leaves (with alum, rain water), lupin leaves (with alum, tap water), lupin leaves (with vinegar, rain water), lupin flowers (with alum, rain water), lupin flowers (with alum, tap water), lupin flowers (with vinegar, rain water), sappan wood (without mordant, tap water), sappan wood (without mordant, rain water), sappan wood (with alum, tap water), sappan wood (with vinegar, rain water), turmeric (with alum, tap water), turmeric (with alum, rain water), indigo + turmeric (with alum, tap water), indigo + lupin leaves (with alum, rain water), sappan wood (with alum, rain water) + lupin leaves (with alum, rain water), sappan wood (with alum, rain water) + indigo.

Plant dyeing deeply resonates with one’s view towards colours. A dyer or an artist cannot guess the exact shade that will be produced through plant dyes but the uncertainty is a key part of the experience. The variables involved make dyeing exciting, as each project will result in new shades and tones. In the end, plant dyeing is gratifying and the end result makes the whole process worthwhile.