a dough begins to think… to feel.

A Concordia University Field School in Iceland

For my personal project while undertaking this residency at the Icelandic Field School, I decided to make a mask. A hand crocheted mask that would allow the wearer to blend into the natural environment and blur the line between “figure” and “ground”. I returned to crochet for the first time since I was a teenager and painstakingly constructed its hooded shape out out of moss stitch (which I loved) and yarn over-slip-stitches (which I detested). I became obsessed with the repetition of the crochet hook. It was refreshing and rewarding to make something useful and wearable (I make paintings for the most part).

When it came to determining the design I would use within the central mask insert, I had dozens of ideas, varying from drawn tracings of wallpaper patterns found within the Kvennaskollin residence we were living within to piecing together an image of the surrounding Bloundos landscape out of scrap fabric. But when our professor Kathleen Vaughan suggested I think about working with the image of grass, the project started to shift. What about creating a mask that would allow the wearer to attempt to camouflage into the grass?

On numerous hikes through the surrounding area with my cohort we had instinctively laid down in the grass, it’s tall tendrils inviting us to be held as well as briefly escape the biting wind at a cliff’s edge. What about creating a mask that would invite the wearer to take this comfort and moment of communing in whatever grass they might find around them? I decided to felt together a loosely interpreted image of grass to fit inside the face hole of the hood, using Icelandic lopi wool and yarn, and miscellaneous fibres.

When I started this project I was mainly thinking about the photographs I would take of myself or others wearing the mask once it was done. But in constructing the mask, putting it on and being inside it and the sensory deprivation it creates; in seeing and photographing others wearing it while also wearing my clothes, I have realized that this project is not just about constructing an image but sharing the act of wearing it.

I titled the project “How to be no one” because this mask invites the wearer to enter a state of positive self-effacement. However, the project is also stronger when multiple people don the mask because it underscores that anyone (and therefore no one) could be inside. Instead of donning a mask and becoming a character, you become something eternal (grass).

Our group exhibition opens tomorrow and I plan to invite visitors to wear the mask and lie in the grass. Hopefully some people will go for it and try to become grass….

Florence Boucher

In the middle of the month of June, I decided to embark on a trip to Akureyri to see the work of the Table Collective with the rest of the group. Everyone was going, and I felt excited by the idea of leaving our tiny Blonduos, seeing the mountains, and feeling the landscape passing by quickly through the car window. Feel the speed again.

The roadtrip was great, hearing friends laughing was a blanket for my heart, and a herd of horses crossed the street, in a dramatic and spectacular manner. It all felt great.

Until!

We arrived in the city, and suddenly my body started to feel out of place. I didn’t know where to go, what I wanted to do. Everyone seemed to have thought of this before: which places they wanted to visit, where the best ice cream was, how to find a cheap fish and chips. Shops, restaurants, streets, cars, supermarkets. City things. Money spending. Yes Flo, Akureyri is a city, and this is where you wanted to go. What did you expect?

I quickly realized that I was not interested in cities since I arrived in Iceland. This feeling was confirmed when I walked an hour from downtown to the camping site, on a road crossed by fields, pastures, a little piece of forest, and breathtaking mountains. I feel a need to be in the tall grass in the middle of nature’s sounds. A silence filled by everything else.

I want to feel like a tiny creature between the mountains and climb them to prove me that I’m big. I need isolation and a huge calm. And not the kind of isolation that distances me from people, but the one that makes me see fewer of them, allowing us to get closer.

I left Akureyri very happy to have seen the Table Collective’s work. I can also say that I enjoyed our little moment in the Botanical Garden, all of us sitting in the grass with live music, having a glimpse of the Icelandic unpredictable summer.

(But yes I was reassured to be back in the silence that I got used to. Not the silence silence, but the birds-howling, wind-blowing, sea-singing silence.)

How sweet, how passing sweet, is solitude!

But grant me still a friend in my retreat,

Whom I may whisper—solitude is sweet. (William Cowper)

🙂

We had only just arrived and already were personally greeted by the sun on our first day, they decided to welcome us to Blonduos with one of the most amazing sunsets I have ever seen and then proceed disappear for the next week leaving us with a storm that was latter described by locals as “the worst weather ever seen in June”. A fine rival for Montreal’s winter.

But then, they came back, not only with their beauty but with their very much appreciated warmth, underneath which we learned how to spin and might even have tanned a little bit.

It is hard to explain what 24h of daylight does to your body and mind, yet I find it even more difficult to describe the feeling of witnessing a sunset at 1am, knowing the sunrise will follow in less than an hour. A never ending spectacle where the sun doesn’t just go down, it sets sideways.

Yet there I was, on the 11th of June, alone on the rocks of the old port of Blonduos, whitenessing what I can surely count as one of the most incredible sunsets I’ve ever seen. (I know I said this about the first one but honestly they just keep getting better)

Suddenly everything is more. Emotions, colors, sound… I am hypnotized by the wavy texture of the eater that looks as if it was an animated film. Extremely grateful for the orange dots that cover the rocks for making the act of sitting so much more interesting. Feel much more connected to the family of ducklings floating in front of me and genuinely wondering how they know when to sleep.

And even though I tried to capture it (I mean I really tried) that kind of beauty is just too much for our human cameras. I will still leave you with some of the hundreds I sent back home, and ask you to imagine a landscape where the beauty is at least 278% greater than them.

Blönduós is the kind of place that makes you wonder, how is this even real?

Lots of Love

Gabi

Sylvie Stojanovski

Go outside–preferably to a location with some plants or trees, like a forest, walking path or ravine.

Find water (a puddle, a river or an ocean).

Once you find water, sit/stand/crouch with water as close as what feels comfortable.

Try not to refer to water as an “it.”

Take a moment to connect with water.

Breathe.

Notice if water makes a sound. Does water bubble, gurgle or swishhhhh?

Reflections are best found in still water–water that patiently waits, and listens back. Though the practice of being with water can happen anywhere. You can only see reflections in still water.

When you find water. Look.

What do you see on the surface of water? What do you see in the depths of water?

Sometimes, instead of reflections, you might see shadows, or ducks, or seaweed on water. That’s okay. Witnessing reflections is a practice that takes patience, and consistency. Reflections are fickle, and ephemeral. They may appear when you least expect it.

Sit/stand/crouch with water. Be with water.

Thank water for existing, for experiencing this moment with you.

Return as you wish.

—

In 2020, I started a walking practice to get outside and connect with the land near my parents’ home while living in isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On my daily walks through the West Highland Creek watershed in Scarborough, Ontario, I became mesmerized by reflections on water–in puddles, rivers, and lakes. I began taking photos and videos to document what I saw–shadows of tree branches, reflections of the sky, pebbles on the ground.

Four years later, I find myself returning to the practice of witnessing reflections (though they are much harder to spot on the Blanda River as water pours out into the Húnaflói bay). In reflections, land meets water meets sky, and I am able to ground myself in the present moment, wherever I am. I hope this practice may find you when you need it most.

Even before arriving in Iceland, the national costume has been a subject of curiosity for me. The long skirts, vests and jackets, all delicately embroidered with intricate metalwork. But atop every outfit is a particular hat. The skotthúfa is a hat that to me, symbolizes the classic Icelandic look. As my travels through Northern Iceland continue, I have become hyper-aware of these hats and have begun to notice their presence in a vast array of contexts.

At the Prophecy Museum in Skagastrond, the gift shop offers a 19th-century style of the hat, which is knit. This version is untraditional in the sense that the artist has incorporated the Icelandic yoke patterns often found in the Lopapeysa Sweater. At this year’s knit fest, booths were selling kits and parts for creating the hat, which is also a testament to its modern popularity.

A visit to the Textile Museum was naturally a treasure trove of skotthúfa’s. Pictured is my favourite costume from the exhibit on the national costume. This hat is one of the newer styles, fashioned from velvet and clipped to the hair with a comb, with a very long tassel hanging down. Further into the museum, in the exhibition on the life of Halldóra Bjarnadóttir is a portrait of the woman herself. In this painting, she wears the skotthúfa along with the traditional Icelandic costume, which is characterized by the large bow of fabric in the front. Both these examples are housed in a location that prides itself on the textile history of the area, so the abundance of skotthúfa is no surprise. However, as we get further from the museum, the hat remains a persistent character.

At the Glambauer Turf House Museum, a museum dedicated to documenting the daily lives of farmers living in the turf houses during the 20th century, there is a room full of portraits. Most are men, but the two women in the room are both sporting the skotthúfa!

Apart from these historical documents, this traditional Icelandic hat also appears in a variety of artistic renderings. At the Fairytale Garden at Oddeyragata 17 in Akureyri, folk artist Hreinn Halldórsson has created fairytale figures out of wood. Many of these are women wearing the Icelandic National costume, including the hat. Pictured are three separate sculptures. The Blonduos Hotel has a framed cross-stitch piece of a woman wearing the national costume, interestingly, the tassel of her hat is the only three-dimensional aspect of the work!

Finally, I found it so intriguing that I made my own version! Tracking the presence of this hat throughout my Icelandic travels has been a fun way of interacting with the culture as well as learning more about the traditional costume. 🙂

– Rebekah Walker

About two weeks into our artist residency some of us started referring to Kvennaskólinn as home. We would say to each other, “I’ll see you later at home”, and “I forgot it at home”, or “I’m going home after the pool”. I saw this as a sign of how quickly we felt comfortable, supported and entrenched in our new routine during the residency: we made the residence ours – even if for only a brief time.

As we settled in, and got to know each other over breakfast, lunch and supper, elements of our personalities surfaced. For instance, early on the dining room table was partially taken over with puzzles that most of use would spend time, which was occasionally frustrating, trying to complete before moving on to another. One resident held marathon sessions late into the night at the table doing one puzzle after another. The table is also where we shared food. A few among us would go beyond sharing a pie bought at the store (nothing wrong with that) and cook big pots of rice and beans, waffles and banana bread pudding. Two potluck suppers with the rest of the group in the second residence led to an astonishing buffet and gave us all a chance to socialize outside of a class structure. These gatherings were not just about breaking bread, but created trust and bonds between us. We shared details about our practice, our experiences and skills, offered help, material and equipment. We became an art collective of sorts as we all created work made-in-place deeply connected to the land and water.

Everyone’s generosity is what stands out for me the most, and not just from the other artists, but also the staff. After explaining to Elsa, the Textile Centre’s director, that I needed a dark space to do my work, she offered me the garage at the textile lab, and she entrusted me with the key so that I could access the space anytime I needed to. This made all the difference in my ability to execute my vision for my project. Then there was Jóhanna, one of the instructors, who showed limitless patients and encouragement while teaching me to spin wool. Project manager, and horse owner, Katharina included us in a horse roundup as a group of residents moved a small herd from one pasture to another. I’ve rarely had the experience to be so close to horses, let alone while they are running at full speed. It was thrilling. Ragnheiður spent hours, and then gave us extra time, to teach us the art of tapestry. In Akureyri, both she and her daughter, Thora, came out to support a group of Concordia students among us who were holding an exhibit. I also really appreciated my conversations with Hanna, the housekeeper, who took such good care of our home.

There were moments, as I walked the halls and interacted with the staff and students on my way to my room, that I wondered if this was what it was like to be Harry Potter at Hogwarts? I may not know any spells, but there was a lots of magic inside this home. Corny, but true.

Instagram: @dalejcrockett

Website: https://www.dalecrockett.com/

The sky here in Iceland is a powerful presence that transforms the day, minute by minute. It may choose to cover the mountains in the distance, as if to hug them tight and let them rest during the endless sunlight. It moves clusters of clouds, exposes the tireless sunshine, shows off its brightest and most vibrant rainbows, and sprinkles raindrops on the hills of green. The Icelandic sky’s best artworks, however, are its magnificent sunsets and sunrises. The pinks and purples mix with the yellows and blues to create the most stunning artworks for all to appreciate.

The sky is alive. It breathes, smiles, cries, and sleeps. Make sure to greet it in the morning, thank it for its energy, be present in its beauty, and love it for all that it is.

Catherine Faiello

During my first week in Blönduós, I had a dream. One of the most vivid dreams I’d had in awhile.

I was standing on what our field school cohort has dubbed “the secret beach”, on the north side of town, past the end of Hafnarbraut (a name I have only just learned from Google maps: I know it as the long nameless road that flanks the ocean and winds past the slaughter house and soup factory). I knew it was the same beach because of the black sand, the craggy rock formation to my right curving into a crescent shore, and the stones threatening to become boulders underfoot.

But the beach was so much larger than the one I’d visited in my body earlier that day. In my mind, asleep in bed, the beach was W-I-D-E, the waves HIGH and relentless, the rocks barriers as much as buoys to brace myself on. The air was blue, heavy with grey. And when I looked around, suddenly there emerged 12-16 or so slick forms from the black waters. They were seals. Glossy and blubberous, awkward yet graceful. All watching me. It felt like they were there for protection but also to communicate some kind of warning. Or maybe just to watch. Should I put on some kind of show for them? I knew one thing for sure: they were no ordinary seals. They were selkies. Their thick skins hiding the faint outline of coats that could be shrugged off at will to take another form.

All of a sudden, the ocean became AN OCEAN and I was flat on my stomach on a bare mattress headed for a waterfall. Being sucked away towards the horizon behind me, l cried out, looking beseechingly to the selkies for help, but they just stared; their eyes empty hollows, equal parts curiosity and sorrow, stuck between worlds.

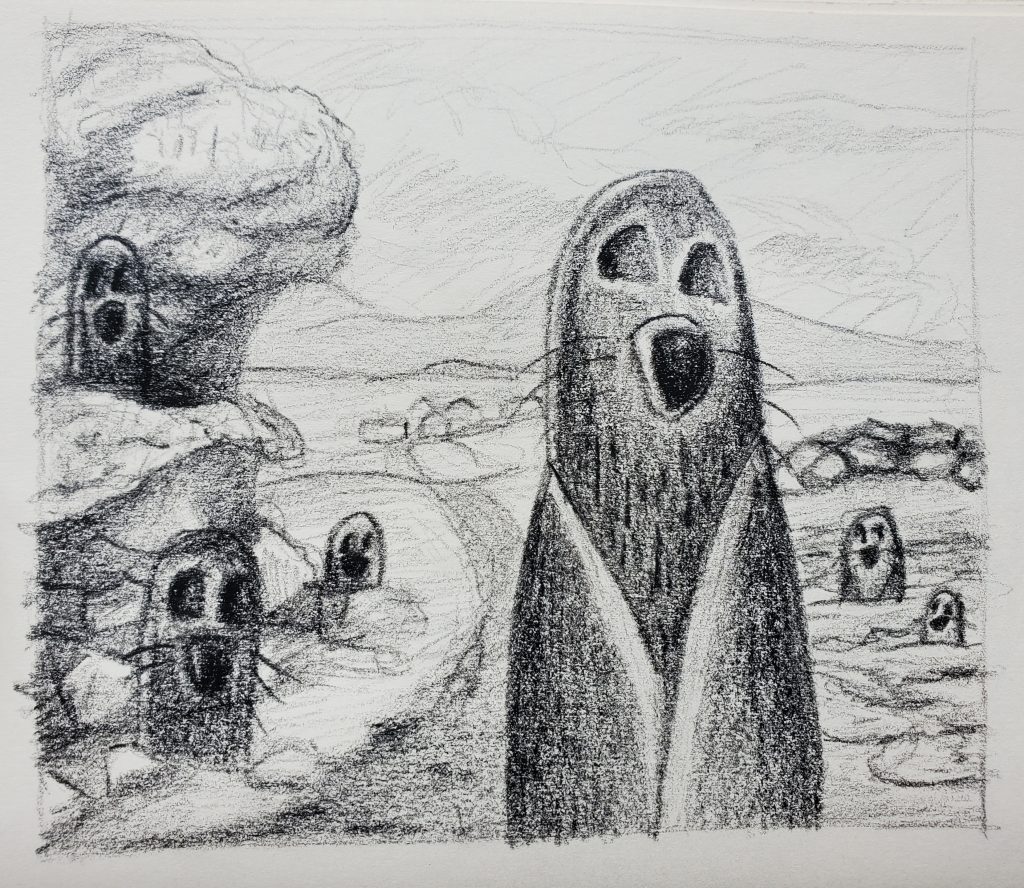

In my drawing of the dream, the selkies came out looking more like moles than seals. Something cartoonish always seems to happen when you try to convey something mysterious in drawing form (or maybe that’s just me and what my hand does). It’s also hard to capture the ambiguity of a feeling or an aesthetic experience with something as concrete as a conté stick. But there’s something about their eyes, or lack thereof, that I got right, especially in the main figure. She knows something that I don’t. A secret about Blönduós that can’t be learned in a month long residency at the Textile Center here. A secret that probably can’t even be learned in a lifetime of living here. A secret held by the land and water for itself. A secret held by and for the selkies.

Adapting and pivoting is an important part, I believe, of growing as an artist. I have learned many things during the residency in Iceland, and the one feature that has had a dominant impact on my art-in-place practice has been learning to embraces the alterations the natural environment has imposed on my practice as I explore the Icelandic environment and unique material found within it.

Setting out with a plan is important to me, but equally important, I’m discovering, is adapting that plan to the elements I encounter along the way. This is not always easy for me. I can get very attached to my plan and see anything short of it as a failure. This approach, I have learned, can deny me the magic and beauty of unforeseen and unexpected results. In Iceland, I am working with natural elements; they are my collaborators, but I can not control the wind, rain, snow, hail or lack of sun that we have experienced while in Blönduós. My work involves creating cyanotypes by using the natural movements of ocean waves or the flow of a stream. During the process I may place material found in the vicinity on the canvas or paper, such as seaweed, sand and rocks, or they may find themselves picked up during the act of submerging the material. Sometimes the wind blows things onto the canvas, sometimes it blows it off, and sometimes a dog, who is very excited to see me, walks all over my work. As with any collaboration, we must work together, make compromises and embrace those unexpected outcomes. That is what Blönduós is teaching me.

Instagram: @dalejcrockett

Website: https://www.dalecrockett.com/