My great-grandmother was considered a master embroiderer during the late 1800s. She made most of her living embroidering fine silk and occasionally clothes for the high ranks of society in China. Her specialty was silk butterflies. However, during the cultural revolution in China, Chairman Mao wanted to create a new visual culture to communicate his ideologies. Much of the traditional art and culture were either destroyed or suppressed. This included embroidery and traditional silk-making. To survive, my great-grandmother and her family focused on weaving instead. This is the story I was told by my grandmother.

Part of the appeal to apply for the Iceland field school was to search for lost connections, histories and new narratives to reconnect with my great-grandmother. Growing up, my sisters were given the opportunity to inherit most of the familial expertise, while I sat watching them. Being the only male child of my parents, I was discouraged from needlework and weaving as it is seen as women’s work. I can’t definitively say this is the reason, but I never subsequently considered incorporating fibres in my artistic practice.

Since my move to Montreal, I’ve been thinking a lot about familial legacies, recalling my childhood memories and my sense of belonging. I started to re-imagining what my family’s life would be like if my great-grandmother had passed down her embroidery knowledge. This curiosity led me to re-trace my family’s history (“her-story”). Multiple attempts led me to many oral stories, but examples of work and records were nowhere to be found; this was partially due to the lack of public historical records in China. I tried to connect the available stories to make sense of it all, hoping to connect to my Chinese roots. In attending the Iceland Field School, I saw an opportunity to create work as an ode to my great-grandmother, a woman that I never met. Additionally, being embedded at the Icelandic Textile Centre, with its rich history as a women’s college, is the perfect location to celebrate and pay homage to all the strong women in my family through my art-making.

Fibres is a beautiful art form used and respected across all cultures, with records spanning over 1000 years. Embroidery connects narratives, builds solid communities, and reimagines threads and yarn into art. With this mindset, I knew I wanted to create a connection between my Chinese Canadian identity with the Icelandic landscapes using fibres. One of my main objectives was to explore and research Yue (Guangdong) Embroidery, a process from the region where my family originates, and its aesthetics as a tribute to my great-grandmother. This exploration led me to discover 7 characteristics of Yue Embroidery:

1. The themes are diverse. The classical theme incorporates landscape painting as its main focus, rendered in light colours. The “Five Ridges theme” is prestige rendered in colour, with symbols of auspicious fruits, animals, flowers, birds, dragons and phoenixes. The “Western theme” is mainly embroidered with gold thread to emulate the Rococo style borrowed from 18th century Europe.

2. Images that incorporate flowers and birds are specialties in Yue Embroidery.

3. Compositions are always symmetrical, composed of negative spaces that allow for more room to add finishing touches.

4. The lines are diverse, and the needles are varied.

5. Colours are contrasted between light and dark.

6. Gold threads are used for the outline of the embroidery pattern.

7. Yup embroidery was traditionally utilized for a wide range of applications, including clothing, quilt covers, pillowcases, scarves and so on.

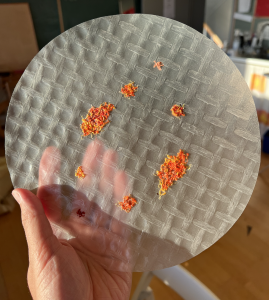

Taking on these principles, I was really inspired to embroider the orange lichen on the Blonduos’ sea wall. A lichen is a life form that has a symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae, similar to the relationship I have with my Chinese and Canadian identity. The bright contrast of the rocks and orange lichen also caught my eye, and it reminded me of my home in Vancouver.

The lichen became the connection between my home and Iceland, so I decided to embroider the lichens on rice paper. Rice paper is a material I’ve been using in my practice and I specifically bought it to use on this journey. One might say rice paper acts as a second skin with water, moulding to the contours of an object as it becomes moist. I wanted to utilize the properties of rice paper to ground a part of myself in the landscape along with my Chinese heritage. I would dip the embroidered rice paper in the Icelandic waters soaking and washing it almost like a ritual. Once the rice paper is moist enough, I found a rock with orange lichen near the sea wall, laid the paper on it and let it mould into shape. The final artwork is both performative and durational, as the rice paper and embroidery decompose and give back to the organisms, nature and the land.

Jacky Lo, MA Student, Art Education