I am dyeing, I answer my faraway friends

met with reddening cheeks and mischievous giggles feasibly rooted in our collective tabooed associations with death and dying.

Explanation unfurls – I am colouring wool and cloth with plants. Mortality loiters elsewhere. Below the shell of this explanation is a knowing that there is a connection between infusing colour upon a neutral, receptive body (cloth or wool) and dissolving sentience and breath (death) – shapeshifting.

a connective tissue,

a single thread within a whole warp,

discreet until it is tugged on,

then a rippling affects the whole

weaving, body

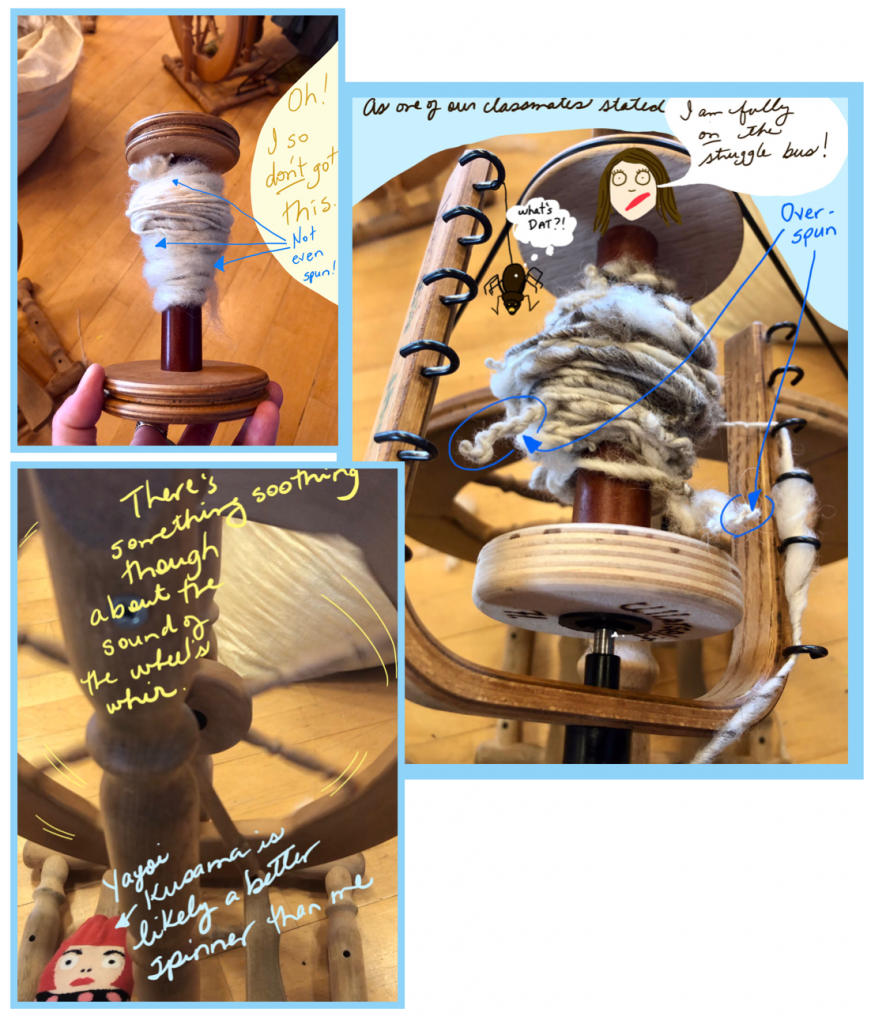

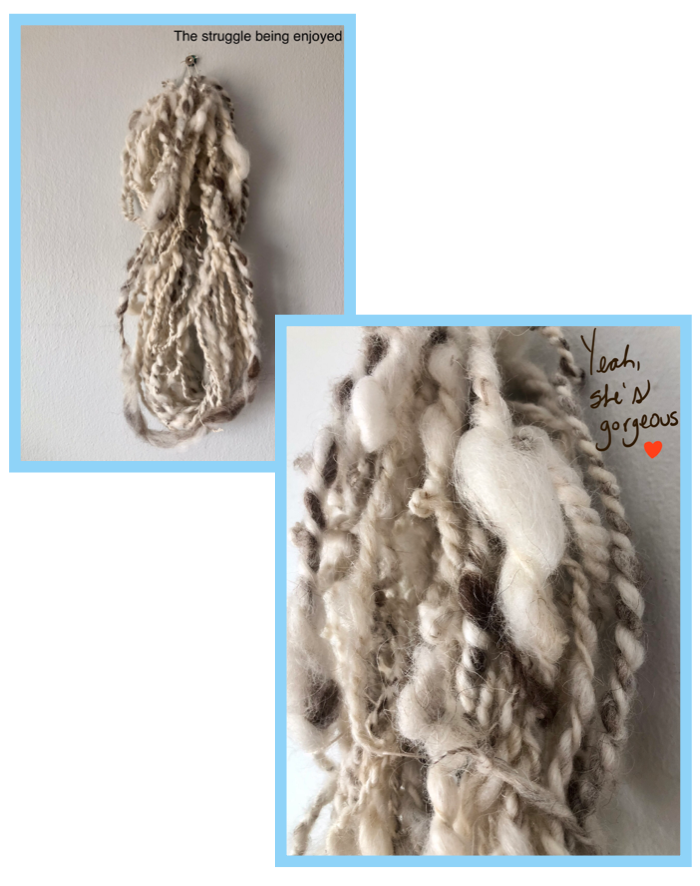

Transformation steeps here.

When we dye a surface, we gather the pigment from a living, growing being. There is something that it is like to be that flower, plant, or root – that we will never know. In the process of colouring the porous fibre body, the plant dies. It is ripped from the soil, the fruiting body is pulled off, the petals torn, the bark stripped. Unfurled.

A death event occurs so as to allow for colour to bloom somewhere else.

The alchemical spiral – cycles embodied in coloured material to make things with.

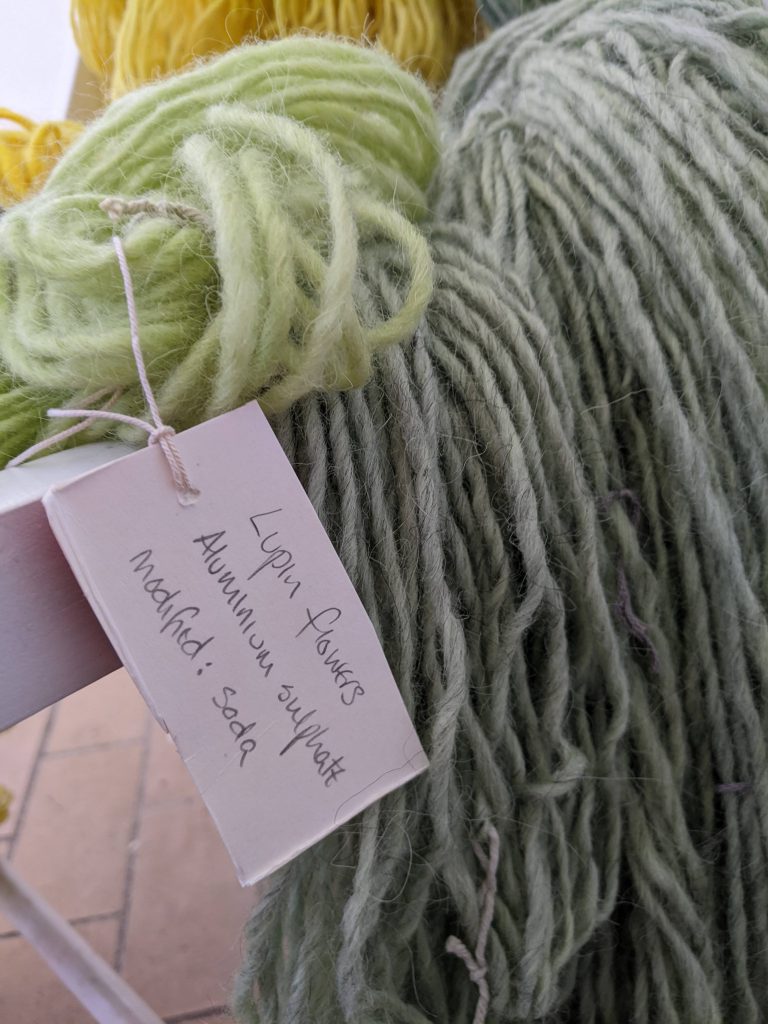

I brought a skein of hand dyed wool from home.

An animated chartreuse yellow skein whose pigment was sourced from the fruiting bodies of wolf lichen – a slow growing algae-fungus found on the bark of dead or dying conifers in high altitudes in the Pacific Northwest. It was named wolf lichen due to its toxicity which was used to ward off or poison wolves (Galun).

Mordanting – the French mordre ‘to bite’, an essential element of the dyeing process. Through the mordant bath, the fibre is prepared usually with salts and heat to prepare it for colour. Wolves mordant too.

In Iceland there are Lupins everywhere. Etymologically, ‘Lupin’ uses the French root loup or ‘wolf’ stemming from Medieval times when the plant was thought to move through a landscape in packs, devouring everything in their path (Collins). We now know the opposite is true. Lupins are considered invasive species in Iceland as they do not originate from this place. However, they are highly adaptable plants – their “rhizobium-root nodules…allow them to be tolerant of infertile soils and capable of pioneering change in barren and poor-quality soils” (Kurlovich and Stankevich).

This characteristic of pioneering change in a barren landscape is a quality I wish to embody. I adore Lupins for this quality alone. Wolf Lichens and Lupins reflect one another – their etymology paralleling wolves, shadowy, poisonous, ravenous, and adaptable as well as the fact that they grow in dying landscapes and bring with them soil fertility and a spectrum of colours.

Bright yellow and pale blue. A palette of wolves.

Julia Woldmo

\\

Sources:

Galun, Margalith (1988). CRC Handbook of Lichenology, Volume III. Boca Raton: CRC. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-8493-3583-3.

Kurlovich, B. S. and A. K. Stankevich. (eds.) Classification of Lupins. In: Lupins: Geography, Classification, Genetic Resources and Breeding. St. Petersburg: Intan. 2002. pp. 42–43. Accessed June 19, 2022.

‘Lupin’ definition and meaning. Collins English Dictionary Online. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/lupin Accessed June 19, 2022.