From the moment you get on the purple WOW Air airbus A330-300 to Iceland, it’s apparent that the Reykjavik based company is selling you an experience. The cabin lights shift from green, to blue, then yellow, mimicking the northern lights that are common in northern countries. The flight attendants are dressed in cardigans and skirts, intensely purple from top to bottom. The pocket in front of you has maps and magazines talking about different Icelandic excursions and destinations, listed with times, costs, and duration.

(www.airplane-pictures.net)

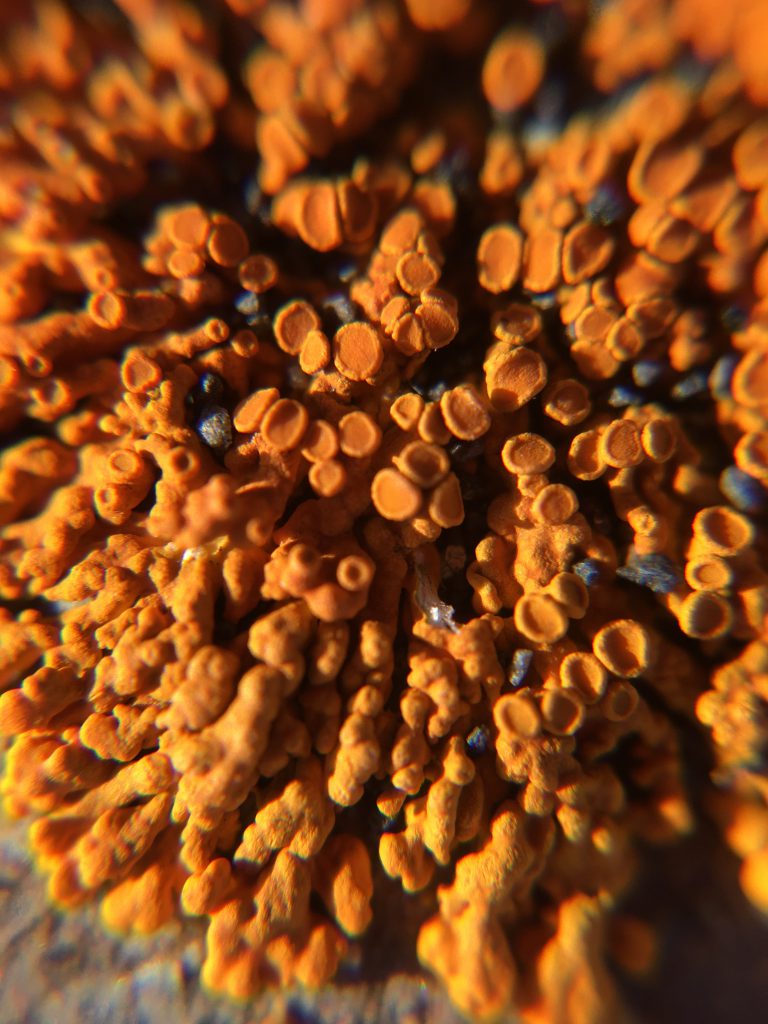

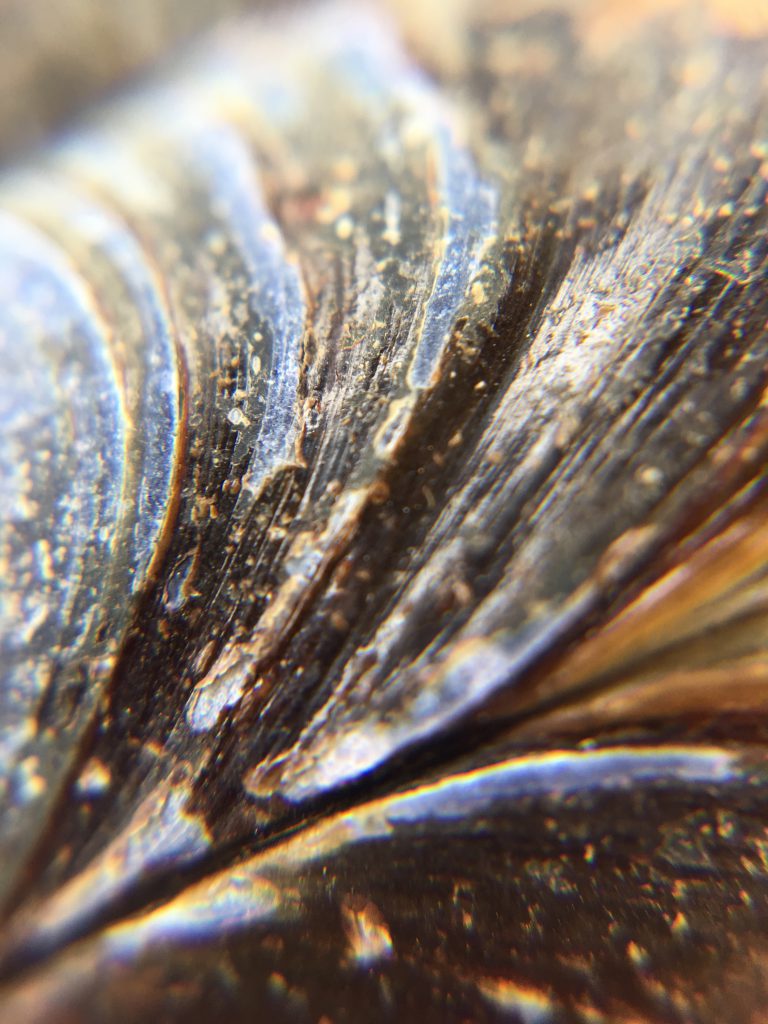

The Blue Lagoon tour is among the most popular and is a geothermal spa on a lava bed. Its website invites us to “experience the wonder” of it’s beauty and vastness. On the golden circle tour, guests are reminded that Iceland is tectonically active, with geysers that erupt several times an hour, a volcano crater, and Thingvellir national park, a long rift where the tectonic plates of North America and Europe meet. On the Into the Glacier tour, one can go by snowmobile or ice vehicle to the ice caves that have been hollowed out at the centre of Icelandic glaciers.

(www.bluelagoon.is)

On the Into the Volcano tour, guests are lowered into the centre of a volcano that erupted 4000 years ago. Both are considered “extremely family friendly”, with only the most basic winter gear required for full enjoyment (and a camera, for those “indescribable” moments!). The tour bus and the extreme looking all terrain vehicles are equipped with full WiFi and USB charging ports, with comfort being a top priority. Behind these experiences is a perceived danger, presenting the landscape as powerful, rugged, and awesome. Iceland has a reputation for being a beautiful place, but I believe that this description of Iceland is miscategorized, as the primary draw to the Icelandic landscape is sublime.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) published A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Beautiful and the Sublime. (1757) Burke argues that the sublime and the beautiful are often considered to be opposite ends of a spectrum but are in fact unalike. He defines both as stemming from passions. Beauty stems from our passion of love, as we find beautiful qualities in flowers, in human bodies, and in pleasing landscapes. Things that are beautiful are often smooth, delicate, and pleasant. The sublime stems from our passions of fear, dealing with the rugged, the unexplored, and the dangerous. Sublime characteristics are found in vastness, infinity, and magnificence. The sublime instils awe by reminding the viewer of an imminent danger and the finality of death, without an actual present danger.

(Wikimedia Corp)

In Reykjavik, I made a friend who later added me to Facebook. She was a lawyer working in the United States and was kind enough to offer me drives to different places in the mornings. She had rented a four-wheeled vehicle to travel on Iceland’s most extreme roads, which allows one to see the most rugged parts of the land. Her posts come across my Facebook feed and present a slew of hashtags, such as #detox #bliss #serenity #bucketlist #wanderlust. The term wanderlust is seen in psychology as the desire for development by experiencing the unknown and confronting the unforeseen. The images presented with these hashtags include vast landscapes and pictures by roaring waterfalls and rocky cliffs. Google, Facebook, and Twitter searches present many more photographs like this, with various travellers presenting themselves near similar Icelandic staples. These sentiments are echoed in both online and print advertisements, such as the ones available in the seat pocket of the big, purple WOW Air Airbus 330-300.

(www.icelandreview.com)

(www.icelandreview.com)

Beauty seems to be only a small consideration of the tourist gaze on Iceland. It appears that those who travel here are far more concerned with an experience, something that transcends imaginations rather than pleases eyes. The concerns here are undoubtedly sublime, placing the visitor face to face with the awesome and harsh realities of natural forces.